With a planned capacity of 500 megawatts, the Spotsylvania Solar Energy Center would be the fifth-largest solar power facility in the United States and the largest east of the Rocky Mountains. Currently, Virginia’s largest solar facility is Southampton Solar, which has a generation capacity of 100 megawatts.

The plans are a sign of not only sPower’s increasing interest in Virginia but of the commonwealth’s increasing focus on solar energy.

Headquartered in Salt Lake City and jointly owned by AES Corporation, a Fortune 500 electric power generator and distributor, and the Canadian Alberta Investment Management Corporation, sPower has been eyeing Virginia for several years.

Microsoft’s ongoing expansion of its data center in Mecklenburg County proved a catalyst, particularly after Microsoft President Brad Smith announced the company’s commitment in 2016 to “build and operate greener data centers” that would “rely on a larger percentage of wind, solar and hydropower electricity over time.”

In November 2017, sPower, operating as Pleinmont Solar, LLC, filed the first documents related to the Spotsylvania project when it applied to Virginia’s State Corporation Commission for certificates of public convenience and necessity for a 500-megawatt solar-generating facility.

Four months later, Microsoft and sPower announced that the tech giant had committed to purchasing 315 megawatts of solar energy from the

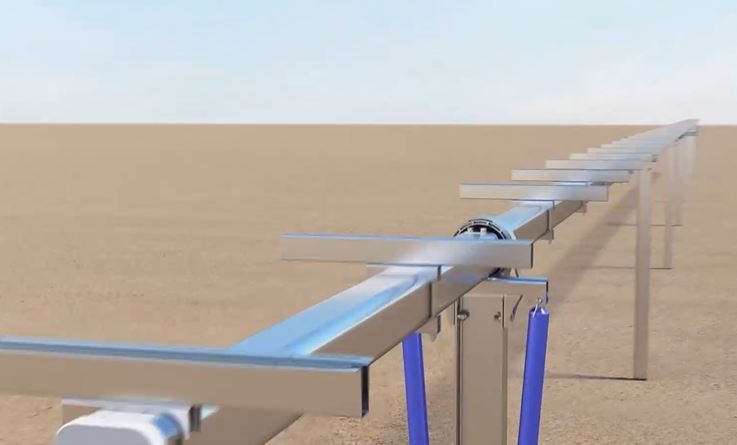

Spotsylvania project in slewing drive what was “the largest corporate solar agreement in the United States.” The deal was hailed by Gov. Ralph Northam as an example of Virginia’s growing role as “a global leader in the clean energy industry.”

At the same time, sPower moved forward with plans for another massive solar facility, this one on 2,270 acres in Charles City County and capable of generating 340 megawatts.

Like the Spotsylvania Solar Energy Center, the Charles City County project, christened the Keydet Solar Project, focuses on agriculturally zoned land used for timber that lies near an electrical substation where sPower can tie into the grid. In October, the Charles City County Planning Commission, on a 5-1-1 vote, and with what one local paper called “minimum resistance,” recommended that the local Board of Supervisors approve the project. (The Keydet facility has not yet gone through the SCC’s review process.)

If passed, the Spotsylvania and Keydet projects would more than double Virginia’s solar capacity, adding 840 megawatts to the 656 megawatts it recorded in 2018. And, according to Menahem, this is only the beginning.

He said that the company has other projects “in development” in the commonwealth, although no others have progressed to the stage of public review.

The Spotsylvania proposal comes at a time when Virginia has set ambitious targets to increase its solar capacity.

Most notably, the commonwealth’s 2018 Energy Plan, produced by the Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy and endorsed by Northam, calls for the development of 3,000 megawatts of utility-owned and utility-operated solar and wind resources by 2022.

Because sPower is classified by the SCC as a “non-utility generator” rather than a regulated public service corporation, the Spotsylvania Solar Energy Center would not count toward this target. It would, however, contribute to another of the energy plan’s major goals: expanding clean-energy options for corporate customers.

“Customer needs are shifting, and a slewing drive number of corporate customers are requesting access to greater levels of renewable resources,” the 2018 Energy Plan concluded.

The Spotsylvania project appears to be an indicator of that rising demand: all 500 megawatts it would produce have already been committed to customers through power purchase agreements. Of those, the largest amount, 315 megawatts, will go to Microsoft. An additional 165 megawatts will go toward a group led by Apple and including cloud delivery platform Akamai, online marketplace Etsy and insurance provider Swiss Re.

The remaining 20 megawatts have been committed to the University of Richmond in an agreement that University Associate Vice President of Finance and Administration Mark Detterick called a “win-win situation”:

“UR will be directly responsible for introducing additional renewable energy onto the grid without incurring the cost of owning or operating a large solar facility,” he said in a statement.

To some locals in Spotsylvania, however, sPower’s plans are more of a “lose-lose” situation.

“All of a sudden farms are becoming these massive scenes of metal and glass. It’s a land grab all across the country,” said McCarthy. “There’s no benefit to us.”

The Concerned Citizens of Spotsylvania, a group that lists 1,100 members on its mailing list and just shy of 800 members in its closed Facebook group, have become the most vocal critics of the Spotsylvania Solar Energy Center. The Citizens have mobilized against the project, speaking against it at

Planning Commission hearings to which they have turned out en masse in red shirts to signal their opposition, writing to their local representatives and sharing information with neighbors in an effort to stop plans from going any further.

The group’s criticisms of the project run the gamut from concerns about increased erosion and traffic during the construction phase to the belief that neighboring property values will decline to fears that toxic substances will leach from the photovoltaic panels into the water.

They also claim the 1,800,000 panels slated to be installed will cause a “heat island effect” raising temperatures around the sites and that sPower will eventually abandon the project, leaving the county to clean it up themselves.

“Something’s got to click slewing drive in people’s heads that this thing is going to be dangerous,” said adjoining property owner Michael O’Bier, who has lived on the western side of the project’s biggest site, Site A, for 32 years.

O’Bier said that while he’s a supporter of solar power in general, “solar’s not the way to go in a residential area.”

“Leave the trees there,” said McCarthy. “It’s designated forestland. We think it ought to stay that way.”

Dave Hammond, another member of the Concerned Citizens who has lived in the Fawn Lake subdivision for about five years, expressed worries about siting such a large facility, with five times the generating capacity of Virginia’s largest installation, Southampton Solar, in an environment wildly different from the desert where most large solar farms are found.

“How they translate to the hills of Virginia is a big unknown,” he said. And the Spotsylvania project is “too big. There’s too many unknowns. It’s too risky.”

In response, Taylor Keeney, a spokesperson for sPower, pointed out that the company operates 17 different solar generation sites in North Carolina, and that “while they are not as large, it has been proven that you can efficiently operate solar projects in our climate.”

“I’m not sure why one in Spotsylvania County would be any different,” she said.

Much of the debate over the Spotsylvania Solar Energy Center comes down to competing information. sPower has issued white papers attempting to debunk many of the claims made by the Concerned Citizens, while the Citizens have embarked on their own program of research.

For example, a viewshed analysis prepared by an solar slewing drive sPower consultant found that “the vast majority of this project will not be visible from adjoining properties, including the Fawn Lake Community,” as a result of vegetative buffers and the existing topography.

And as far as the contention that the company will just leave the panels and other infrastructure to rust in place after the solar development’s anticipated 35-year life span, sPower pointed out that it is required to file a decommissioning plan with the county.

“Following the term of the project contract, a decision will be made to extend the life of the project or to decommission the project,” the white paper says.

“If the project is decommissioned, sPower will be responsible for removal, recycling and disposal of all solar arrays, inverters, transformers and other structures associated with the project. The project site will be restored in a manner consistent with land use policies in place at that time and in accordance with Spotsylvania County regulations.”

As for hazardous materials in the panels themselves, the white paper points out that the cadmium in the panels — in the form of cadmium telluride — will not dissolve into groundwater in the event of breakage or melt in the unlikely event of a fire.

Even if the panels were pulverized, sPower says, any risk to the environment is minimized because of how difficult it is to leach the cadmium out of the panels. The company notes that “aggressive extraction” is required to leach cadmium during recycling, which involves “crushing the panels into

millimeter-scale pieces and agitating it in sulfuric acid or similar acidic solution,” a process that “in no way” mimics “the actual environment or broken or cracked panels at solar energy facilities.”

Property values are another point of contention. An independent study commissioned by sPower and conducted by local appraiser and expert witness Chris Kaila found that “there is no consistent negative impact to adjacent property that is attributed to proximity to an adjacent solar farm.”

McCarthy, however, said that the Concerned Citizens had conducted their own research on property values and had calculated an estimated 5 percent loss in property values of the homes surrounding the site. That, he said, could lead to annual losses in county tax revenue of $330,000, with losses of $30 to 80 million over the life of the project.

“So far as I’m aware, there hasn’t been clear evidence suggesting that these projects have any demonstrable impact one way or another on property values,” countered Harry Godfrey, executive director of the pro-solar Virginia Advanced Energy Economy group.

On fiscal matters, sPower is firm: “From a very direct economic impact, we will be paying 30 times the property tax starting in year 1 from what the property pays today,” said Menahem. The company estimates that the project would have a cumulative direct impact on county revenues of $17.6 million and would employ almost 850 employees during construction and 34 full-time-equivalent jobs once the site is operational.

Some of the Concerned Citizens think the claims are exaggerated.

The financial windfall of the project is “nowhere near what sPower’s saying it is,” said O’Bier. If the project is approved, he said he would think about selling his land, although “nobody I know is going to buy it.” He even approached sPower with the proposal (“Buy me out and I’ll shut up” is how he described his stance), but they turned it down.

To McCarthy, most of the concerns boil down to improper siting.

“If there’s a huge field somewhere that’s really remote, fine,” he said. But “something of this scale, it just doesn’t belong in a residential, rural, agricultural, historic county like Spotsylvania.”

Not all Spotsylvania residents share the Concerned Citizens’ worries about the proposal. More than 100 have written to county supervisors expressing their desire for the Solar Energy Center to be built. Many of these letters cite the need to wean the nation off its dependence on fossil fuels and move toward renewable sources of energy while praising the revenue and jobs that sPower has promised to bring to the county.

To Dave Wilson, a county resident who has lived off West Catharpin Road on the western side of Site A for 25 years, many of the arguments against the solar facility are “irrelevant.”

Of the 6,350 acres that sPower has agreed to solar tracker actuator purchase if the project is approved, 4,575 acres are owned by Riveroak Timberland, which has been operating in Spotsylvania since 2000. Riveroak has publicly announced that regardless of the outcome of the solar project, it will be selling its land and has endorsed sPower as the “best fit,” one that “fits perfectly with the feel of Spotsylvania.”

“The reality is that something will be developed on our land,” Riveroak president Bill Ridge wrote in an op-ed in the Free Lance-Star this past December.

“Whether it’s another neighborhood, mixed-use development, apartment complexes, industrial warehouses, an RV and ATV park, campground, or another type of business, it is NOT going to stay as a tree farm.”

Given that reality, Wilson says, the Solar Energy Center “is the least invasive of any of the options that are going to happen to the land.”

Another residential development, he said, would be the “worst-case scenario,” requiring massive expansions of infrastructure and services. Other industrial projects would likely be more intrusive than solar facilities, which mostly operate passively once constructed.

Ironically, some of the same concerns about preserving county character were voiced by Spotsylvania residents in 1991, when the Fawn Lake community itself was being built.

To Hammond, one of the opponents of the project, the Planning Commission’s recommendation that the county approve only one of the Spotsylvania Solar Energy Center’s proposed three Photovoltaic holder sites — the smallest one, generating only 30 megawatts of solar power — has “a lot of wisdom.”

“I think that’s a good place to start,” he said. Anything larger “might change the character of the county.”

Looking forward, Godfrey sees the Spotsylvania project as an illustration of the challenges of building such facilities on “greenfield” sites, a term used for rural or agricultural land being developed for the first time.

“If the state could find more ways to make it easier for developers to work on brownfield sites, then I think we can avoid some of the conflicts that can occur when developers are building elsewhere,” he said.

Still, he added, “The conflict that we’ve seen arise in Spotsylvania isn’t necessarily indicative” of how solar development will occur statewide. “It just has to do with particularly community dynamics.”

Revolutionising sugar mill efficiency: Mill Gears unveils world’s largest gearbox

Revolutionising sugar mill efficiency: Mill Gears unveils world’s largest gearbox

who are the leaders in solar trackers for the power industry?

who are the leaders in solar trackers for the power industry?

Trina releases new version of Vanguard 1P solar tracker

Trina releases new version of Vanguard 1P solar tracker

GameChange Solar Tests Tracking System for 40-Year Lifespan

GameChange Solar Tests Tracking System for 40-Year Lifespan